Comprendere e superare l’Anoressia Nervosa (AN)

Visto da una prospettiva evoluzionistica, gli individui e le loro famiglie non devono addossarsi la colpa dell’anoressia nervosa. Piuttosto, studiare gli interessanti cambiamenti biologici può aiutare le famiglie e i terapeuti a lavorare insieme per combattere questa malattia.

L’anoressia nervosa è il disturbo psichiatrico più omogeneo, ma i suoi stereotipati sintomi sono il contrario di quello che ci si può aspettare da una persona affamata. Nonostante le persone con anoressia siano per almeno un 15% al di sotto del peso normale, si sentono comunque piene di energia e rifiutano i cibi che si utilizzano per tentarle. Questa misteriosa malattia è stata attribuita a problemi psicologici del singolo o della famiglia, o a disfunzioni biologiche.

Ciechi del proprio corpo

Per quanto strano possa sembrare, quando le persone iniziano a sviluppare l’AN, esse non si rendono conto che qualcosa non va, poiché il loro corpo gli invia falsi segnali. Ad esempio, le anoressiche sottopeso non si rendono conto di essere troppo magre.

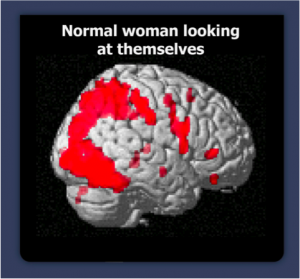

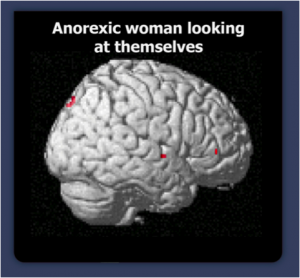

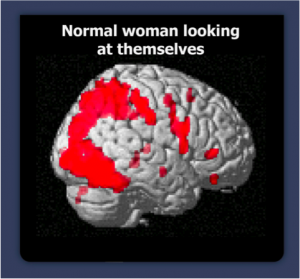

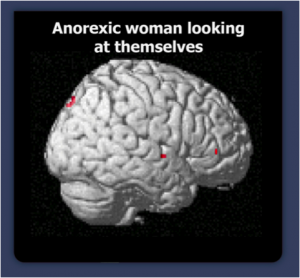

Questa foto di brain-imaging mostra il pattern di attivazione della corteccia visiva quando le donne guardano altri corpi e quando invece guardano se stesse allo specchio.

Come queste immagini mostrano drammaticamente, quando le persone con AN ci dicono “non riesco proprio a vederlo”, stanno dicendo la verità. La corteccia visiva è letteralmente cieca ai loro corpi, mentre la regione cerebrale responsabile dell’immagine corporea è iperattiva e riempie ininterrottamente il vuoto con una versione più grassa del corpo stesso.

Questa strana cecità si ha solo su un corpo anoressico, e solo quando lui o lei sono sottopeso.

Come si comporta un cervello anoressico?

Questa non è l’unica cosa strana che un cervello anoressico fa. Profondamente nel cervello, in un’antica regione chiamata ipotalamo, succede qualcosa di molto strano. L’ipotalamo monitora lo stato nutrizionale e manipola il nostro appetito per farci mangiare. Normalmente, quando le persone sono affamate, l’ipotalamo aumenta i segnali di fame mantenendo bassi i segnali di sazietà, in modo che se il cibo è disponibile, ne possono godere.

Normalmente, quando la gente è affamata, i rewards del cervello nei confronti del cibo sono mantenuti alti, per incoraggiare la ricerca del cibo stesso. Per esempio, il corpo accende i recettori degli oppioidi, facendo sì che il cibo diventi come un’iniezione di droga. Questo aumenta i recettori cannabinoidei, rendendo così il sapore del cibo come se ti fossi drogato.

La dopamina, la sostanza chimica del cervello che gioca un ruolo chiave nell’orgasmo e nella dipendenza, si innalza bruscamente quando una persona affamata mangia. Se questo ti suona come il fatto che il mangiare quando si è affamati determini il rilascio di una vera farmacopea di droghe da strada, hai ragione. La maggior parte delle droghe che creano dipendenza, sfruttano i sistemi di ricompensa che per primi si sono evoluti per assicurare che gli animali mangiassero.

Mentre alcuni cambiamenti cerebrali aumentano i rewards per il cibo, altri cambiano le nostre scelte. Partiamo dal presupposto che noi controlliamo ciò che mangiamo, ma chi è a dieta sa che c’è di più. Come il bisogno dell’ aria o dell’ acqua, la fame di cibo può alterare irresistibilmente la volontà anche del più forte, così che alla fine una persona si decide a mangiare.

Ma questo sistema è alterato nei pazienti con anoressia nervosa, così che se pur affamate, scelgono di non mangiare. Ciò avviene determinando cambiamenti ad ogni livello del potente sistema di regolazione energetico del corpo. L’ipotalamo anoressico abbassa i segnali di fame e aumenta quelli di sazietà, così che i pazienti con anoressia si sentano disgustati dal cibo e si sentano pieni dopo piccoli pasti. I segnali di sazietà sono inoltre aumentati attraverso tutto l’intestino, così che le persone con anoressia si riempiono velocemente.

Nei centri di reward del cervello, gli oppiacei, gli iniziatori dei cannabinoidi e i recettori della dopamina sono diminuiti, così che il sapore dei cibi non è gratificante.

Nei circuiti emozionali del cervello, l’anoressia produce ansia e sensi di colpa nei confronti del cibo, e di orgoglio quando i pazienti riescono a resistere alla fame; l’anoressia fa credere alla persona affamata che controllare il proprio appetito è di vitale importanza. Eppure, allo stesso tempo, due dei più importanti segnali di fame nell’ipotalamo sono alti come in una situazione di normale senso di fame, così che i pazienti anoressici si ritrovano a pensare costantemente ai cibi che loro non possono mangiare.

I comportamenti e i sentimenti degli anoressici sono stati a lungo visti da medici e terapeuti come una perdita di controllo della dieta. Secondo il Manuale Diagnostico e Statistico dei Disturbi Mentali, l’Anoressia Nervosa è il risultato di una “ricerca instancabile della magrezza” e un “rifiuto di mantenere un peso corporeo normale”. I pazienti anoressici si ritiene siano vuoti e nevrotici –“fame di attenzione” o “sciopero della fame – e i loro genitori sono sospettati di essere controllanti e ipercritici.

Non ci sono evidenze scientifiche per queste ipotesi. Attenti studi non hanno trovato alcuna prova per specifici problemi emotivi di anoressia nelle famiglie colpite, e la tipica anoressica, prima della malattia, era attiva, competente e coscienziosa.

Ci sono una serie di altri fattori che non quadrano con l’idea che l’anoressia nervosa è causata da problemi psicologici. L’anoressia nervosa è genetica. I ricercatori hanno identificato diverse mutazioni genetiche legate a comportamenti anoressici e di alterato appetito e di alterata attività delle molecole regolatorie; significativamente, questi geni sono accesi quando il peso corporeo diminuisce. I sintomi principali dell’anoressia – difficoltà nel mangiare, iperattività e distorsione dell’immagine corporea- non variano attraverso gli individui, le epoche storiche, il sesso, l’età e la cultura, cosa che ci si aspetterebbe se i sintomi dell’anoressia fossero una risposta simbolica a conflitti personali. Invece, i sintomi principali sono in accordo con una biologica risposta alla fame.

Infine, ciò che gli anoressici sono in grado di fare – mantenere il loro peso inferiore al 15% o più rispetto al normale, è molto notevole dal punto di vista biologico. I ricercatori che studiano la regolazione energetica affermano che è impossibile per gli individui fare questo a lungo.

Perché noi pensiamo che una ragazza di 14 anni può testardamente resistere alla fame, mentre gli adulti no?

Neuroscienziati (e genitori) sanno che la parte del cervello che ci aiuta ad esercitare autocontrollo non è completamente matura fino a che le persone non raggiungono i 25 anni.

Infatti, il rifiuto del cibo nell’anoressia non è dovuto ad una forza di volontà. Quando le persone con anoressia cercano di guarire, si rendono conto che il loro corpo e la loro mente combattono tra loro.

Come Kari Chisholm ha scritto in Hungry Hell: “ Ci vuole molto autocontrollo per perdere peso, ma molto di più per recuperarlo di nuovo.”

Adattato a fuggire la carestia

Solo coloro che hanno una propensione genetica possono sviluppare anoressia nervosa se affamati o molto sottopeso.

Ma perché alcune persone hanno certi geni?

Allo stesso tempo nella storia dell’uomo, i sintomi dell’anoressia devono esser stati selezionati come una utile risposta contro la minaccia di morte per fame.

Normalmente, le persone affamate sono fameliche, stanche e demoralizzate; conservano l’energia e si focalizzano nella ricerca del cibo. Ma considerate le sfide che i nostri antenati cacciatori-raccoglitori hanno dovuto affrontare, solo poche decine di migliaia di anni fa.

Quando i foraggeri nomadi ebbero esaurito il cibo locale, e le catene montuose, gli oceani o i deserti proibirono i viaggi più lunghi, le normali risposte alla fame (la letargia, che conservava l’energia, la fame che motivava la risoluta ricerca di cibo e la loro consapevolezza di essere deperiti) avrebbero interferito coll’intraprendere un difficile e spaventoso viaggio.

Se alcuni raccoglitori affamati sono stati in grado di ignorare la loro fame e spostarsi con energia, loro sono probabilmente sopravvissuti a costi più elevati rispetto a coloro che sono rimasti. Per questi speciali membri del gruppo, l’autoinganno riguardo l’immagine corporea, riguardo le riserve di grasso, e a come i loro corpi fossero impoveriti, avrebbe realmente fornito l’ottimismo per viaggiare.

I tratti della personalità autocontrollante e coscienziosa (entrambi oggi associati all’anoressia), potrebbero anche aver aiutato gli esploratori a persistere nei loro viaggi disperati, con una piccola speranza di aver successo. Io chiamo questa spiegazione evolutiva dell’anoressia: l’ipotesi dell’adattato a fuggire la carestia.

La Marcia dei Pinguini

L’ipotesi dell’adattato a fuggire la carestia può sembrare impossibile da provare, ma molti tipi di prove lo supportano. La natura dà a molte specie la capacità di sviluppare l’anoressia ( intesa come mancanza di fame), quando cioè potrebbe competere con altri doveri della vita. Se avete visto il film “la Marcia dei Pinguini”, sapete che l’Imperatore dei pinguini deve diventare anoressico per procreare; i maschi possono perdere metà del loro peso corporeo mentre covano! Anche altre specie mangiano di meno per migrare o per difendere un territorio riproduttivo.

Come gli umani, i ratti ed i suini evolvono come foraggeri onnivori e diventano anoressici e attivi quando hanno fame. I ricercatori che studiano gli animali attribuiscono questo comportamento all’istintivo tentativo degli animali di lasciare le aree prive di cibo. I suini allevati per essere magri sono vulnerabili a sviluppare l’anoressia se perdono ulteriore peso per via dello stress dovuto alla separazione dalla madre o al bullismo con gli altri suini. In laboratorio, se si usano ruote di esercizio, i ratti affamati ignorano il loro cibo per correre. Nonostante i ratti normalmente corrono meno di un miglio (1-2 Km) al giorno, questi ratti frenetici percorrono circa 12 miglia (20 Km) al giorno come se cercassero di andare disperatamente da qualche parte. Se consentito, questi ratti in gabbia alla fine muoiono di autoinedia.

Ci sono evidenze che la gente preistorica viaggiava davvero per lunghe distanze? Negli ultimi 50.000 anni gli uomini hanno viaggiato in ogni parte abitabile della terra. Nella Preistoria, gli uomini erano già ampiamente più distribuiti rispetto a qualsiasi altro mammifero. Inoltre, questi antenati erano talmente degli efficaci cacciatori che cacciavano ripetitivamente le indigene popolazioni di prede. Ciò portò alla carestia locale e dovettero così migrare in cerca di nuovo cibo. Solo le persone e i gruppi che migravano colonizzavano nuovi mondi. Gli antenati degli odierni pazienti anoressici potrebbero essere stati quelli che sono andati alla ricerca di terre migliori per la tribù.

La maggior parte dei preistorici cacciatori-raccoglitori non fecero lo stesso nel nuovo continente.

Solo 500 delle persone che hanno lasciato l’Africa ha dato origine alla popolazione moderna del resto del mondo. Secondo la ricerca genetica molecolare, la popolazione fondatrice degli Indiani di America potrebbe essere stata solo di 70 individui. E, gruppi con membri anoressici erano apparentemente tra i fondatori.

L’anoressia nervosa è estremamene rara tra gli Africani; è più comune tra gli Europei e gli Asiatici e appare più comune nei Nativi Americani che hanno viaggiato il più lontano possibile dall’Africa.

Sport estremo

Le persone anoressiche riferiscono di sentirsi come se non fossero tenute a mangiare. Si vergognano di cedere alla fame. Ciò appare loro giusto quando fanno restrizione e attività fisica ed è estremamente difficile ragionare con loro sulle loro convinzioni. Nonostante questi comportamenti sembrano essere scelti dai pazienti, questi ultimi dicono di essere “comprati” dall’anoressia. Colpisce il fatto che persone così diverse come gli Indiani delle riserve, le ragazze della scuola media, ragazzi sottopeso e donne anziane, esprimono gli stessi bizzarri pensieri e sentimenti quando si ammalano di anoressia.

Questi atteggiamenti anoressici sembrano senza senso, illogici per chi non è anoressico, ma noi accettiamo e addirittura lodiamo gli atleti che esprimono lo stesso tenace impegno nel praticare il proprio sport. Questa può essere una situazione simile all’anoressia. Non è più necessario cacciare il cibo e difendere fisicamente la propria famiglia, ma la maggior parte delle persone si sentono costrette ad esercitare le proprie abilità atletiche, incoraggiano i figli a farlo e amano profondamente guardare le gare di atletica.

I nostri atteggiamenti nei confronti dello sport sono probabilmente un retaggio evolutivo dal tempo in cui l’abilità di una persona nell’abbattere o nel correre poteva salvare un’intera tribù dalla fame o in battaglia. Noi chiamiamo addirittura “eroi” certi atleti. Io credo che, sia l’atteggiamento degli atleti verso una sofferenza duratura, sia gli atteggiamenti degli anoressici verso il resistere alla fame, sono stati selezionati perché hanno aiutato i nostri antenati del Pleistocene a sopravvivere.

Ma perché gli atteggiamenti delle persone anoressiche dovrebbero essere innescati oggi, in un mondo pieno di cibo? Noi potremmo ugualmente chiederci perché le persone diventano obese quando non c’è alcun bisogno di immagazzinare ulteriori grassi. Se i tuoi antenati sopravvivevano alle frequenti carestie immagazzinando grassi nei momenti in cui c’era disponibilità di cibo e se questa abilità è stata ereditata, l’ipotalamo può fare del tuo corpo una riserva di grassi extra, nonostante la tua conscia consapevolezza di abbondanza.

L’ipotalamo, che si occupa di bilancio energetico e di acqua e di altre nozioni di base sulla sopravvivenza, non riceve informazioni dalla parte pensante del cervello, ma piuttosto attraverso il monitoraggio del sangue. Poi, in base alle regole dettate dall’evoluzione, avvia i cambiamenti nel metabolismo energetico, nell’appetito, negli atteggiamenti e nei comportamenti, per dare al corpo ciò di cui ha bisogno.

Questo potente sistema di regolazione dell’energia è la ragione per cui chi è a dieta alla fine finisce per riacquistare il peso perduto. Noi possiamo provare a dire al nostro corpo che non ci sono motivi per accumulare grassi in più, ma l’ipotalamo non può sentirci. Allo stesso modo, sei i tuoi antenati sono sopravvissuti alla carestia grazie alla migrazione, l’ipotalamo legge il fatto che il grasso corporeo sia basso come un segnale per levare le tende e partire. E allora si inganna relativamente alle tue riserve di grasso, si costringe a controllare l’appetito e ti spinge a muoverti. Tu puoi ammalarti di anoressia nervosa se perdi abbastanza peso per qualunque motivo. All’ipotalamo non interessa se il peso è stato perso per un’influenza, iperattività o dieta.

Perché le femmine anoressiche sono più dei maschi?

E’ comunemente assunto che le ragazze e le donne sono molto più suscettibili all’anoressia poiché cercano di assomigliare a modelli sottili a livelli anoressici. Le femmine anoressiche sono sempre in numero maggiore rispetto ai maschi, anche in epoche quando essere magra non era la moda.

Nonostante l’idealizzazione della nostra cultura di livelli non sani di magrezza porta certamente a mettersi a dieta e si inizia a percorrere un po’ la strada dell’anoressia e altri disturbi alimentari, si scopre che gli standard di magrezza non sono la ragione principale della differenza tra i sessi. Infatti, fino al 1930, i resoconti storici non avevano nemmeno descritto una “ricerca della magrezza” come motivazione per l’anoressia nervosa. Storicamente, il digiuno è stato associato alla pietà religiosa, non all’apparenza. Diari e altri resoconti di prima mano mostrano che molte persone consideravano sacro nella storia (quindi soprattutto le donne) mostrare i sintomi tipici dell’anoressia, restrizione, iperattività, negazione della fame, nonostante essi non esprimevano la moderna paura delle persone anoressiche del grasso.

Prima della pubertà molti sia ragazzi che ragazze (in egual numero) sviluppano l’anoressia. Dopo la pubertà nove femmine sviluppano l’anoressia per ogni maschio. I ricercatori hanno trovato una mutazione genetica su un recettore degli estrogeni che aumenta la capacità di sviluppare anoressia nelle ragazze durante la pubertà. La frequenza di questa variazione genetica indica che, quando questo gene è stato selezionato, è stato più adattativo per le femmine in età riproduttiva sviluppare l’anoressia, piuttosto che per le ragazze in prepubertà , i ragazzi o gli uomini.

Ancora una volta, la vita dei nomadi cacciatori-raccoglitori può spiegare perché. Se un uomo e una donna incontravano un altro gruppo mentre essi erano alla ricerca di cibo, la donna aveva più probabilità di sopravvivere. Anche se venivano catturati, lei avrebbe potuto ugualmente riprodursi. Così in generale era più sicuro per le femmine viaggiare. Ricerche sulla genetica molecolare hanno scoperto che le femmine migravano infatti molto più lontano rispetto ai maschi nel nostro passato evolutivo. Le femmine di ratto inoltre sviluppano anoressia più velocemente rispetto ai maschi, forse per la stessa ragione evolutiva.

Ma è davvero possibile che gruppi di cacciatori raccoglitori avrebbero permesso alle giovani donne di andare in giro alla ricerca di cibo? Non erano queste culture anche più sessiste e rigide riguardo i ruoli e le attività delle donne rispetto alla nostra? In realtà, secondo gli antropologi, ragazze e donne hanno sempre aiutato a fornire il cibo per le loro famiglie. Le società di agricoltori cacciatori erano in realtà molto più egualitari ed aperti alla piena partecipazione delle donne rispetto alle società agricole e statali.

Ma, penso che la prova più convincente che siano state le giovani donne a guidare i loro gruppi affamati è la storia di Giovanna d’Arco. Era una contadina analfabeta nella Francia medievale, una cultura feudale, patriarcale. Eppure, principi e generali la seguirono. Giovanna aveva tutti i classici sintomi dell’anoressia: era molto magra, mangiava notoriamente molto poco, aveva un’incredibile energia e non aveva il ciclo.

Bruciata viva

Le persone con anoressia nervosa spesso fanno chilometri con davvero poco cibo. Possono gli anoressici in qualche modo sfruttare la prima legge della termodinamica, prendendo energia dal nulla?

No. Nonostante le persone con anoressia si sentono forti e grasse, questa è un’illusione. Se l’anoressia nervosa diventa cronica, i malati moderni, come San Giovanni, vengono bruciati vivi dai loro stessi corpi. Il corpo affamato cannibalizza i propri muscoli, il proprio cuore ed i propri organi. Gli anoressici soffrono di insufficienza renale, insufficienza cardiaca o convulsioni, passano tutto il loro tempo a spiegare che non sopportano mangiare. Nel corso del tempo, le persone con anoressia attiva diventano rattrappite e consumate.

Le ossa, svuotate di calcio, sono così fragili che una donna con cui ho lavorato si è rotta il femore tirando una palla da bowling; un’altra si è rotta la caviglia scendendo da un cordolo. Anche se per un breve periodo,l’anoressia compromette la salute. Se il disordine persiste per oltre quattro mesi, è compromessa la crescita in altezza del bambino.

Se l’anoressia nervosa dura troppo a lungo, la maggior parte delle persone finiscono per abbuffarsi e poi purgarsi. I ricercatori usavano pensare che diverse tipologie di personalità avrebbero portato o alla bulimia o all’anoressia, ma ora sembra che la bulimia spesso accompagna o segue l’anoressia, probabilmente perché il normale adattamento alla fame – fame rabbiosa e capacità di ingozzarsi- progredisce di volta in volta e le persone si ritrovano ad abbuffarsi. Se la persona anoressica poi vomita, digiuna o fa attività fisica per sottrarsi alle abbuffate, questi rimedi perpetuano i segnali neuroendocrini che causano fame incontrollabile e si da così il via ad un circolo vizioso di abbuffate e purging.

Quando l’anoressia nervosa diventa cronica, le persone esauriscono i loro benefici di assicurazione medica, i loro amici, le famiglie e loro stesse.

L’anoressia alla fine porta ad una vita così miserabile che il rischio di suicidio è 50 volte in più del normale. Nel 1991 un tribunale olandese ha respinto le accuse contro un medico che aveva assistito al suicidio di una donna di 25 anni, con una storia di 16 anni di anoressia, in quanto conclusero che “la donna stava soffrendo in modo insopportabile e senza prospettive di miglioramento”.

L’anoressia richiede che tutto venga sacrificato; amici, coniugi e figli diventano di secondaria importanza rispetto al bisogno di muoversi, di evitare di mangiare o di rigettare il cibo già mangiato.

Le persone care prendono le ricadute come qualcosa di personale, mentre le giustificazioni imploranti il ”bisogno di controllo” delle anoressiche, fanno sì che le famiglie si allontanino dai pazienti. L’assunzione che le vittime rifiutano di mantenere un normale peso porta molti a biasimare le vittime per la loro situazione. Nella società di oggi, l’anoressia nervosa rende le sue vittime riservate, solitarie e fragili.

Intrappolati dall’ANA

Una tipica anoressica è una ragazza di 14 anni che è sempre stata magra ed attiva. Perché le ragazze di 14 anni sono più vulnerabili? Con la pubertà le ragazze hanno raggiunto la loro statura adulta, ma non sono ingrassate. Sono in genere più magre che in qualsiasi altro momento nella loro vita. Ora, come i suini allevati per essere magri descritti sopra, questi “manici di scopa” sono a rischio di sviluppare l’anoressia nervosa se perdono un po’ di peso per qualsiasi motivo, sia per malattia, attività fisica o dieta.

Alcune delle mie giovani pazienti sono convinte di non avere l’anoressia nervosa poiché esse non hanno mai provato a perdere peso. Ma, purtroppo, hanno tutti gli altri sintomi psicologici e neuroendocrini, tra cui l’incapacità di vedere quanto sono magre, difficoltà nel mangiare, fino ad arrivare all’attività fisica. L’anoressia intrappola le persone per anni.

Tuttavia, l’anoressia non è limitata ai giovani. Se avete la predisposizione genetica a sviluppare l’anoressia, quest’ultima può essere attivata ogni volta che il grasso corporeo diminuisce troppo. I momenti pericolosi si verificano durante le fasi transitorie della vita, che bloccano l’appetito o che inducono a mettersi a dieta: il primo anno di college, gravidanza e nascita del bambino, incontri con i vecchi compagni di scuola, divorzio e morte di un coniuge, e la solitudine o la malattia nella vecchiaia.

Poiché l’anoressia infonde ad un comune mortale poteri apparentemente soprannaturali, può anche riaffermarsi quando il proprio senso di sé è minacciato. Se una persona si sente di non avere il controllo del suo lavoro, del matrimonio, dei figli, mettersi a dieta per raggiungere un peso anoressico può far sentire la persona di nuovo in carica. I pensieri e gli atteggiamenti anoressici si mantengono in qualunque problema psicologico che la persona ha; questa è probabilmente la ragione per cui gli specialisti in disturbi alimentari rimangono convinti che sono i problemi psicologici a causare il disturbo.

Giovanna d’Arco: lei ha dato tutto

Giovanna era sportiva, dura e coraggiosa. “Lei è arrivata dal nulla ed ha dato tutto”, ha detto il biografo Mary Gordon. Poiché “lei sapeva giustamente di essere pienamente capace e di essere stata scelta dal Signore”, fu in grado di convincere il francese Dauphin di darle il comando di una truppa di soldati. Secondo un altro biografo, marina Warner, la sua “gloriosa incoscienza” ispirava gli uomini a seguirla. Lei ignorava la fame e la fatica, e forzava se stessa ad una severa attività fisica. Per terminare l’assedio su Orleans, Giovanna d’Arco e i suoi soldati viaggiarono per 350 miglia in 11 giorni, attraversando 6 fiumi mentre sfuggivano ai loro nemici. Durante la prima battaglia, quando lei fu ferita al petto da una freccia, il comandante francese immaginò che la battaglia fosse finita. Ma Giovanna rifiutò di ritirarsi. Pregò brevemente, rimontò sul suo cavallo e alzò la sua bandiera. Gli inglesi rimasero sbalorditi; i soldati francesi furono incaricati di occupare la città.

Lo straordinario coraggio di Giovanna d’Arco, anche quando feriti e d’inferiorità numerica, stimolò i suoi seguaci ad una serie di vittorie improbabili. Gordon ci dice: “l’effetto che Giovanna aveva sul debole e vacillante Charles è una specie di metafora del suo effetto sull’intero regno di Francia”. Come il suo leader, il regno era demoralizzato, depresso e diviso al suo interno…Improvvisamente, una giovane, sfrontata creatura apparve dalla campagna.”

In quei momenti di disperazione la Francia necessitava di un leader senza paura, la cui fiducia zelante in quest’ultimo avrebbe potuto infondere speranza.

L’energia fisica di Giovanna d’Arco probabilmente deriva dalla sua anoressia, ma lei interpretava le sue straordinarie capacità come parte del volere di Dio nei confronti della Francia. I raccoglitori del Pleistocene avrebbero interpretato le loro capacità anoressiche come parte della loro ricerca per il cibo. Le anoressiche di oggi si intendono in termini di magrezza, “sciopero della fame”, o necessità di controllo.

I genitori sono i peggior assistenti

Nel 1874 Frances Gull, il medico che ha dato il nome all’anoressia nervosa, osservò che quando i pazienti tornavano a casa, spesso perdevano il peso che avevano acquistato in ospedale. Concluse che “i genitori sono i peggior assistenti” dei propri figli anoressici. Questo modella di prendersela con i genitori per le ricadute e la malattia stessa è continuato. Il teorico più importante del ventesimo secolo, Hilde Bruch ha scritto che le anoressiche erano “impegnate in una lotta disperata contro il sentirsi schiavizzate e sfruttate” dalle proprie madri. I medici consigliavano una “genitori-ectomia”. I genitori dovevano smettere di esercitare pressione sui figli per farli mangiare e dovevano lasciar svolgere il lavoro ai professionisti. Ancora oggi, la maggior parte dei medici danno ancora per scontato che il “rifiuto” del cibo rappresenta una lotta per l’indipendenza. I medici possono supporre che un padre assente porti la figlia a “morire di fame per ricevere attenzioni”, o che una madre è talmente controllante che il cibo è l’unica cosa di cui sua figlia può prendere il comando.

Accusare i genitori si è rivelato avere degli effetti deleteri e talvolta mortali. Alcune famiglie sono state gravemente danneggiate, e alcuni bambini, alienati dal sostegno dei propri cari, non sono riusciti a guarire. In “Slim to None: A Journey through the Wasteland of Anorexia Treatment” Gordon Hendricks ha utilizzato il diario di sua figlia Jennifer per narrare del trattamento che si concluse con la sua morte. L’amore del padre era stato etichettato come incestuoso, quello della madre come competitivo ed era stato consigliato ai genitori di tenere le distanze. Il terapeuta era talmente convinto che i sintomi di Jennifer fossero simbolici che lei compromise il lavoro della dietista? Dopo dieci anni passati a lottare contro la malattia, Jennifer morì sola. Oggi i genitori sono stati prosciolti. Studi di popolazione non sono riusciti a trovare la relazione ipotizzata tra la patologia famigliare e lo sviluppo dell’anoressia. I genitori dei pazienti anoressici hanno un’ampia gamma di capacità e atteggiamenti genitoriali, ma come gruppo non sono più controllanti, critici o assenti di altri gruppi di genitori. Recentemente, ricercatori di genetica hanno studiato gemelli omozigoti ed eterozigoti ed hanno concluso che l’ambiente famigliare ha un effetto “trascurabile” se un bambino sviluppa anoressia. Noi sappiamo che i genitori non possono rendere i loro figli anoressici più di quanto non possono renderli autistici o schizofrenici; queste sono tutte malattie biologiche. Ma perché i genitori sono presumibilmente incapaci di prendersi cura dei propri figli anoressici? Una ragione potrebbe essere il fatto che i genitori fanno quello che un buon genitore fa: ascoltare. Imparare a leggere i segnali del bambino riguardo all’essere affamato o pieno è una delle prime abilità che un buon genitore sviluppa. Forzare un bambino a mangiare di più quando è pieno vuol dire non essere dei buoni genitori. Una malattia che inganna il bambino a credere di essere pieno, mette i genitori in una posizione innaturale di non ascolto. Credo che i genitori possono essere dei “cattivi assistenti” esattamente perché essi sono talmente sensibili all’angoscia dei loro bambini, e per una persona con anoressia, mangiare può essere straziante.

Chiunque abbia provato ad implorare, persuadere e convincere un anoressico a mangiare conosce la sicurezza, la tristezza e l’intellettualizzazione di prima mano dell’anoressia. I cari si accollano il peso della disperazione dell’anoressia. Abbiamo a che fare, dopotutto, con i parenti di Giovanna d’Arco, discendenti di chi –con autocontrollo e risolutezza- ignorava la fame e sopravviveva. Chi poteva andar contro Giovanna d’Arco? Non la madre o il padre. I suoi fratelli si unirono alla sua causa.

Eppure, se il vostro bambino fosse terrorizzato dalle iniezioni ma fosse costretto a farle perché necessarie, tu lo conforteresti e supporteresti mentre prende la medicina di cui ha bisogno. Chi è guarito dall’anoressia afferma che “ mangiare nonostante la paura” è stata la cosa più difficile che abbiano mai fatto. Quando i propri cari hanno l’anoressia, il nostro compito è di aiutarli a sopportare l’intensa angoscia nel resistere alle richieste dei loro corpi anoressici. Noi riconosciamo la loro ansia e premiamo il coraggio di cui hanno bisogno per mangiare, nonostante tutto.

C’è bisogno di un villaggio

Gli essere umani sono profondamente sociali, e quando l’anoressia si è evoluta, la gente viveva in gruppi, legati da vincoli di sangue e di responsabilità. L’anoressia nervosa è stata probabilmente più facile da “spegnere” in quel contesto di gruppo. Le società di cacciatori-raccoglitori condividevano il cibo. Quando il cibo divenne disponibile dopo la carestia, il ringraziamento e l’alimentazione rituale di un altro portava a rompere il digiuno. Poichè l’anoressia si è evoluta nel contesto di gruppi interdipendenti, l’aiuto degli amici e della famiglia può essere fondamentale per la guarigione – parte del processo di trattamento dell’anoressia che gran parte del nostro mondo moderno ha dimenticato.

E’ probabile che le anoressiche sono state una minoranza nella maggior parte dei gruppi; questo è basato sulla sua attuale prevalenza. Ciò potrebbe aver funzionato a vantaggio di tutti. Quando le risorse erano esaurite e la tribù era disperata, l’energia dell’anoressica, l’ottimismo e la grandiosità poteva mobilitare gli altri membri a marce eroiche. Quando una tribù affamata raggiungeva una nuova terra di caccia e raccolto, il sostegno della maggioranza dei membri non anoressici avrebbe, a sua volta, aiutato i membri anoressici ad iniziare di nuovo a mangiare. Oggi la maggior parte della gente che è guarita attribuisce la guarigione al supporto dei propri cari.

Il mio corpo sta cercando di migrare

Per 800 anni i malati di anoressia nervosa sono sembrati essere in cerca di controllo delle loro vite. Per i santi anoressici c’era un controllo dei desideri corporei. Per gli anoressici Vittoriani, si pensa, ci fosse un controllo della sessualità. Nella seconda metà del XX secolo si presume fosse il controllo delle dimensione del corpo o di una personale autonomia.

Ma per te, che oggi lotti con questa malattia nella tua famiglia, concentrarsi sul controllo può diventare una trappola. Puoi sostituire il mantra “E’ l’unica cosa che posso controllare” con “il mio corpo sta cercando di migrare”, e con questa nuova visione impara a guarire e rimanere così per tutta una vita piena e produttiva, I pazienti e le loro famiglie non sono impotenti contro il potere dell’anoressia; infatti, con la conoscenza della malattia, loro possono acquisire gli strumenti per combatterla.

Dr. Shan Guisinger è una psicologa clinica nella città di Missoula, Montana. Ha scritto sulle basi evolutive del sogno, dello sport, dei disturbi alimentari e delle relazioni interpersonali. Gli articoli possono essere scaricati su shanguisinger.org

210 N Higgins Ave, Ste 310

Missoula, MT 59802

406-542-8138

shanguisinger.org